Sudden Death: A Reflection

What would you think if you suddenly died unexpectedly? You might think of many things left undone. People you wanted to see, farewells you wanted to say. Sudden death refers to dying within 24 hours of symptoms appearing, not due to accidents or suicide. Although there are no exact statistics, it is said that about 90,000 people die suddenly in Japan each year, more than ten times the number of traffic fatalities. Sudden death is more common in older individuals and tends to affect men more, but it can occur at any age, including students and people in their 20s and 30s.

Many Cases of Sudden Death Are Preventable, Yet Often Not Prevented

Are you aware that most cases of sudden death are preventable? If they could be saved, these individuals might live much longer. However, currently, there are significant barriers to saving people from sudden death, resulting in many lives ending prematurely. Let’s consider how we can increase the survival rate from sudden death and eliminate deaths without farewells.

Sudden Deaths Often Occur at Home

According to the research by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, most sudden deaths occur during sleep, followed by while bathing, resting, or during bowel movements. This means that sudden deaths are by far more common at home than outside. If the early signs of sudden death could be detected at home, it might lead to lifesaving interventions.

Why Are Sudden Deaths More Common at Home?

You might wonder why sudden deaths occur more frequently at home, where one is supposed to relax. One reason is that during sleep, bathing, or bowel movements, there can be a sudden switch between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, leading to rapid vital changes. Another reason is that if someone collapses at work or outside, they are usually around people who can quickly call for emergency services or administer lifesaving measures. In contrast, many people are alone at home during certain times or in certain spaces. Even in homes where three generations live together, younger family members may be out at work or school during the day, leaving elderly individuals alone. Even when family members are home, they may not notice if someone collapses while asleep, bathing, or using the toilet. This is especially true for those living alone, who may die without anyone realizing. The issue of sudden death at home reveals various societal challenges in Japan.

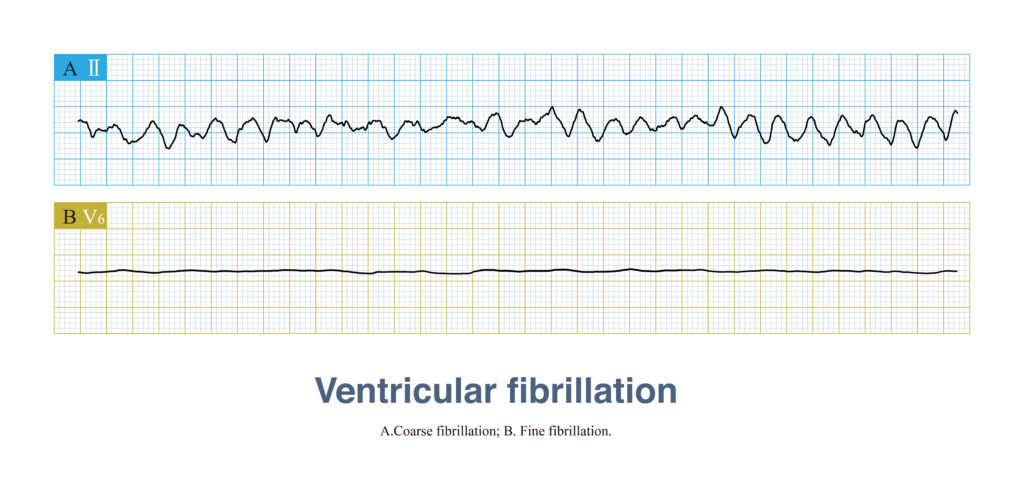

The Majority of Sudden Deaths Are Due to Heart Disease

Over 60% of sudden death cases are attributed to heart conditions, with the majority resulting from ventricular arrhythmias (like ventricular fibrillation and sustained ventricular tachycardia) leading to cardiac arrest. These are often referred to as “sudden cardiac deaths.” It is reported that in Japan, approximately 70,000 people die annually from sudden cardiac death, which equates to about 200 people per day, with over 70% of these cases occurring at home. Reducing the incidence of sudden cardiac deaths at home could drastically decrease the number of overall sudden deaths.

Sudden Cardiac Death Can Be Prevented, But Time Is Critical

Defibrillation Can Save Lives

It’s widely known that sudden cardiac death can often be prevented through defibrillation if done promptly. Defibrillation involves delivering an electric shock to the heart to stop the irregular heartbeat and allow a normal rhythm to resume. For those with ventricular fibrillation, consciousness is lost within approximately six second safter cardiac arrest, leaving no time for the individual to seek help themselves. This underscores the critical role of bystanders in initiating lifesaving actions. In Japan, while many are quick to call for an ambulance, unfortunately, few are prepared or knowledgeable enough to perform defibrillation or CPR, presenting a significant barrier to saving lives.

The Critical Window for Resuscitation

If resuscitation efforts begin within one minute of cardiac arrest, there’s a 95% chance of survival. This rate drops to 75% if actions are taken within three minutes, potentially avoiding brain damage. After five minutes, survival rates plummet to 25%, and the likelihood of brain damage increases. By the eight-minute mark, chances of survival are significantly reduced. This timeline highlights the urgent need for immediate action—there’s simply no time for hesitation or consultation.

Ambulances Often Arrive Too Late

Regrettably, in Japan, calling for an ambulance immediately does not always equate to a high rate of successful resuscitation; only about 7% of those who suffer cardiac arrest outside of a hospital are saved. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, the national average time from emergency call to ambulance arrival was about 10.3 minutes in 2022. This delay signifies that, currently, immediate emergency response often falls short of the critical window for effective intervention. While the presence of an ambulance ensures professional medical intervention, the critical vital first steps to survival are best initiated by those at the scene.

A Side Note: Is Reducing Ambulance Response Time Feasible?

Over the years, the response time for ambulances has unfortunately increased. In 2022, the average was approximately 10.3 minutes, a significant rise from 6 minutes in 1996. This increase is partly due to non-emergency calls which occupy emergency services, thus delaying responses to critical situations. Of course, traffic and housing conditions (such as high-rise buildings and narrow alleys) also play a role. Since these conditions cannot be changed quickly, the first step must be to alter the emergency awareness of all Japanese people; without this change, it seems challenging to reduce the response time of ambulances.

Key to Preventing Sudden Cardiac Death: Swift Use of AEDs

The Lifesaving Role of Defibrillation

Defibrillation is crucial for stopping the chaotic electrical activity in the heart during ventricular fibrillation. By applying an electric shock, defibrillation seeks to halt this irregular rhythm, allowing the heart to spontaneously resume a normal beat. There are two main types of defibrillators:

- Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICD): These devices are surgically placed inside the body to automatically detect and correct ventricular fibrillation, offering a self-contained treatment without the need for external intervention. ICDs are recommended for individuals at high risk of sudden cardiac death, under stringent conditions such as severe heart failure or specific electrical abnormalities in the heart.

- Automated External Defibrillators (AED): Portable devices designed to diagnose and treat life-threatening arrhythmias through defibrillation. AEDs guide the user through the process via voice instructions, making them accessible to the general public and crucial for immediate response in public places.

The Reality of Defibrillation in Sudden Cardiac Death

While the Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) is used for individuals at high risk of sudden cardiac arrest, most sudden cardiac deaths occur among those who do not need an ICD or have not been undergoing heart treatment. Therefore, Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) play the primary role in saving lives from sudden cardiac death. AEDs are commonly placed in public spaces, sports facilities, schools, and commercial venues. Following the use of an AED, administering cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), which includes chest compressions and artificial ventilation, can help restore the heart’s ability to circulate blood throughout the body.

Time Is of the Essence, Yet Public Use of AEDs Significantly Boosts Survival Rates

Because every second counts in saving a life from sudden cardiac arrest, the use of Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) by bystanders can dramatically increase the chances of survival. If an AED is applied within 3 to 5 minutes of cardiac arrest, survival rates can approach 70%. According to a study by the Fire and Disaster Management Agency in Japan, the one-month survival rate for cardiac arrest patients where bystanders did not use an AED was 9.7%. In contrast, when bystanders utilized an AED, the survival rate soared to 42.5%. This significant data shows that even when including cases where an AED was used after 5 minutes, bystander application of AEDs can quadruple survival rates compared to scenarios where no AED is used.

Current State of Sudden Death Resuscitation in Japan

The Extremely Low Post-Cardiac Arrest Survival Rate in Japan: The Paradox of the World’s Highest AED Deployment and Low Usage Rate

Japan boasts the world’s highest deployment rate of AEDs, with about 600,000 units installed across the nation since their general public use was authorized in 2004. Despite this impressive figure, the actual usage rate of AEDs remains low at about 5%, contributing to Japan’s extremely low resuscitation success rate. The survival rate after cardiac arrest in Japan hovers around 5%, starkly contrasted by Seattle, USA, where the rate is between 30 to 40%. This discrepancy highlights the vital importance of immediate CPR by bystanders at the scene, underscoring what sets Japan and Seattle apart in their emergency response success rates.

Why AEDs Are Seldom Used by Bystanders

A survey conducted by the Tokyo Fire Department in 2014 revealed that the primary reasons for bystanders not performing immediate lifesaving actions were “not knowing what to do” and “fear of doing something wrong and being held responsible.” These responses underline two major barriers: a general lack of emergency medical knowledge and experience among the public, and a fear of legal repercussions if the rescue attempt fails.

Lessons from Seattle

What makes Seattle different? About half of its roughly 600,000 residents have undergone training in lifesaving knowledge and techniques, indicating a widespread community knowledge and readiness to act in emergencies. Additionally, the seamless cooperation between bystanders and emergency medical services, often guided by phone instructions from dispatchers, plays a critical role. The “Good Samaritan Law” in Seattle protects individuals who attempt to provide emergency medical assistance, encouraging more people to take action without fear of legal consequences. This law significantly reduces hesitation among bystanders, contributing to the high rate of successful interventions.

Change Is Possible in Japan

Ignorance is a natural barrier to action. Educating the public on how to respond to emergencies, including making lifesaving courses more accessible and mandatory for businesses, sports organizations, and schools, could be a key strategy. Such training should focus on lowering the mental barrier to action rather than cramming complex medical knowledge. Simplification is critical; the aim is to prepare individuals to act promptly in unexpected situations without preparation. Additionally, widespread understanding that well-intentioned rescue efforts are legally protected could lower the threshold for bystander intervention. Introducing laws similar to Seattle’s “Good Samaritan Law” in Japan could significantly encourage more people to act in emergencies, potentially saving many lives.

The Greater Challenge of Addressing Sudden Death at Home

The Difficulty of Home-based Sudden Death Intervention

Despite our best efforts in public spaces, the home remains a formidable frontier in the battle against sudden death. The solitary nature of many of these incidents, coupled with the absence of immediate medical intervention, makes it a uniquely challenging scenario.

Why AEDs Are Rarely Found in Homes

The stark reality is that, even though sudden cardiac deaths most frequently occur at home, the installation rate of AEDs in residential settings is dismally low. This is primarily because large-scale studies have shown that placing AEDs in homes does not significantly increase survival rates. This revelation may seem counterintuitive at first glance, but it’s important to consider the nature of sudden cardiac arrests. Within about six seconds of an event, the individual loses consciousness, making it impossible for them to use an AED on themselves. Even in households where multiple generations live together, there are often times when the elderly, who are at higher risk, are alone because the younger generation is out at school or work. Furthermore, the instances when sudden death is most likely to occur — during sleep, bathing, or in the toilet — are times when even cohabitants are less likely to notice the emergency promptly.

For more details, visit Home Use of Automated External Defibrillators for Sudden Cardiac Arrest

The Growing Challenge of Single-Person Households in Japan

Complicating matters is the global trend towards more single-person households, a pattern also observed in Japan. According to the 2020 census, single-person households account for 38.1% of all households in Japan, a 3.4% increase from five years prior and nearly double from 19.8% in 1980. This demographic shift presents a considerable challenge for home-based emergency interventions. In most cases, unless a friend or family member happens to be visiting, there’s no one present to act during a sudden death event, leading to a grim outcome. Thus, rescuing individuals living alone from sudden death poses a significantly difficult challenge.

Innovating Solutions: Prediction and Wearable Defibrillators

Creating Solutions Based on Understanding the Facts of In-Home Cardiac Arrest

Reiterating a critical point, if ventricular fibrillation occurs at home, consciousness is lost within about six seconds, rendering the individual incapable of using an AED themselves. Thus, if no one is around, the situation likely leads to death. Exceptionally, those with an implanted cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) can be automatically defibrillated even when alone, thanks to the device. However, ICD implantation is an invasive procedure requiring the insertion of electrodes into the heart, limited to high-risk individuals. In essence, for the average person, experiencing ventricular fibrillation while alone at home, during a bath, or in the toilet equates to a fatal outcome. To address this, solutions must be developed based on this harsh reality.

The Ideal: Predicting Ventricular Fibrillation

Predicting ventricular fibrillation could significantly improve conditions for saving lives, potentially increasing survival rates dramatically. The precision of the prediction and the timing before an episode could expand the options available for lifesaving interventions.

Prediction Minutes or Hours in Advance

If predictions minutes or hours in advance become possible, the rationale for having an AED at home changes. The imperative becomes to carry the AED and move to a location where people are present. While calling for an ambulance might be an option if the prediction is highly accurate, given the average ambulance response time of about 10 minutes in Japan, moving to where people are present becomes crucial. For those unable to move quickly, contacting a neighbor or someone living nearby to come over is necessary. Creating a mutual assistance network among neighbors or residents of apartment buildings can enhance reliability and speed. For apartment buildings with a manager, contacting the manager could also be a promising method. Although specifics depend on the living environment, even a few minutes of forewarning could enable the construction of new lifesaving mechanisms.

Uncertain Timing of Prediction

For predictions with uncertain timing—perhaps occurring within the day, a few days later, or even the following week—carrying an AED at all times is impractical. Hence, the current model of stationary AEDs may not be suitable. Additionally, it’s not feasible to always be in the presence of others while awaiting a potential episode, nor is it practical to have someone accompany you at all times. Hospitalization might offer peace of mind, but whether this is feasible depends on the country’s healthcare system and might be challenging. In such cases, a wearable automatic defibrillation device could offer a solution. The Wearable Cardioverter Defibrillator (WCD) already exists as a wearable automatic defibrillator designed for temporary use. Further details are compiled below.

Wearable Cardioverter Defibrillator (WCD)

The Wearable Cardioverter Defibrillator (WCD) is a type of defibrillator that you wear. It features electrocardiogram electrodes and defibrillation electrodes inside a vest, which is worn directly against the skin. The detection of life-threatening arrhythmias and the administration of defibrillation treatment, along with the circuits and battery that control them, are all located outside the body, making it a wearable life-saving device. No surgery is required for its use. WCDs are primarily used temporarily in situations where implantable defibrillators cannot be immediately installed, or when there is a transient risk of life-threatening arrhythmias that requires monitoring and potential treatment. In Japan, the use of WCDs is limited to a period of three months. Since the system is entirely external, it avoids the complications that can arise from surgically implanted treatment systems. However, the wearer can remove it, and it requires frequent battery changes and charging of spare batteries. Additionally, it must be removed during bathing or showering.

For more details, visit Wearable cardioverter defibrillator

Developing New Wearable Defibrillators That Overcome the Limitations of WCDs

The Wearable Cardioverter Defibrillator (WCD) has several critical disadvantages that make it less convenient and more uncertain compared to the Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD). These include:

- The device does not provide protection when not worn.

- It requires the wearer to be always prepared to respond to alarms.

- It cannot be used while bathing.

- It necessitates daily battery changes.

- There’s a risk of injury to nearby individuals during an electric shock.

- Non-compliance with usage instructions may limit the therapeutic effect.

- The need for constant attention to the device’s alarms can be a burden to the patient.

Overcoming these limitations of the WCD and making it as user-friendly as a smartwatch could usher in an era where a wearable defibrillator is a common fixture in homes, especially if the capability to predict cardiac arrest becomes feasible.

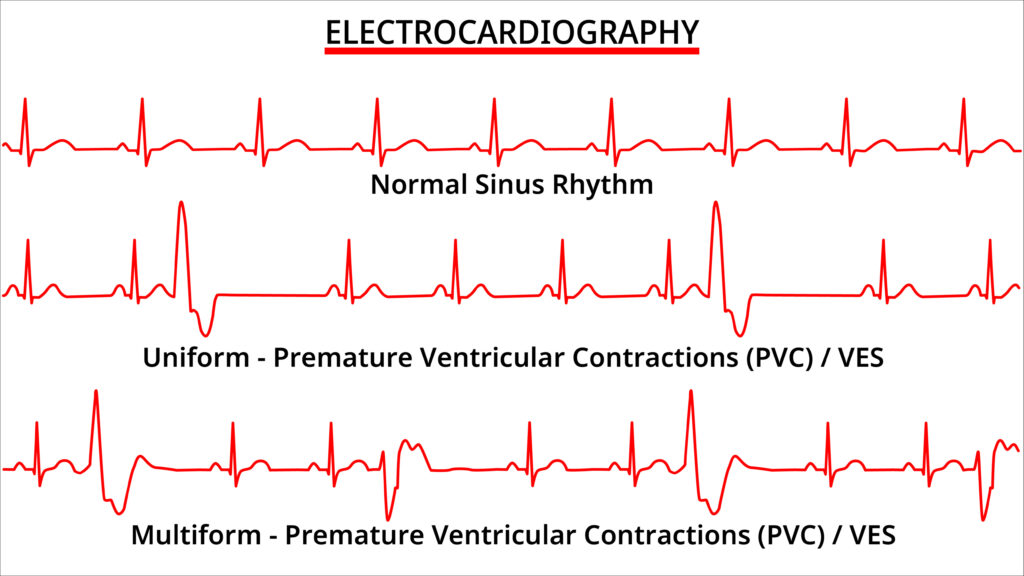

The Current State of Research on Predicting Ventricular Fibrillation

Certainly, the significance of predicting ventricular fibrillation is widely acknowledged, with research focusing on phenomena such as premature ventricular contractions. However, it’s fair to say that the outcomes have yet to meet the high expectations. It’s suggested that precursors to ventricular fibrillation can include symptoms like dizziness, feeling faint, palpitations, shortness of breath, chest pain, a sense of impending doom, experiencing a type of palpitation never felt before, and even fainting. The presence of these warning signs invariably indicates some malfunction in the heart’s operation. If these signs can be accurately captured, it would potentially pave the way for the establishment of predictive methods for ventricular fibrillation.

The Future of Ventricular Fibrillation Prediction Research: Approaching Prediction through Home Monitoring and AI

Promising Results

Encouraging research outcomes have emerged. It has been demonstrated that ventricular premature contractions detected with 15-second single-lead ECGs, similar to those used by smartwatches, strongly correlate with the occurrence of ventricular fibrillation and heart failure. Ventricular premature contractions, especially when they occur in succession or in patients with structural heart diseases such as a history of myocardial infarction, are known to increase the risk of transitioning to ventricular fibrillation. While not directly predictive, this result suggests that wearable devices can detect changes that may lead to ventricular fibrillation.

For more details, visit Premature atrial and ventricular contractions detected on wearable-format electrocardiograms and prediction of cardiovascular events

The Potential of Wearable Devices and AI

The occurrence of premature ventricular contractions does not necessarily lead to ventricular fibrillation. It’s a phenomenon that can even be observed in healthy individuals, complicating the prediction of cardiac arrest. It suggests that there are potentially malignant premature ventricular contractions that easily progress to ventricular fibrillation and benign ones that do not. Identifying these requires continuous, long-term electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring of a large population, a task uniquely suited to wearable devices. The study period would need to span years to capture a sufficient number of ventricular fibrillation events within the cohort. AI analysis of the collected data could differentiate the types of premature ventricular contractions based on their likelihood of leading to ventricular fibrillation, paving the way for predictive capabilities.

The Limitation of Smartwatches at Home

A significant drawback of wearable devices is that they are not always worn at home, where sudden deaths are most likely to occur. For instance, most people do not wear watches while sleeping or bathing, which are prime times for sudden death. Although individuals at high risk of ventricular fibrillation, such as those with a history of myocardial infarction, might wear these devices continuously, the general population is less likely to do so. This highlights the need for alternative home monitoring technologies or wearable devices.

Alternatives to Smartwatches for Home Use

When considering items commonly worn at home, clothing, shoes, or indoor footwear come to mind. Research has been conducted on integrating ECG measuring devices into these items. For example, the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Japan has announced smart wear capable of ECG monitoring simply by wearing it. However, the necessity to remove these items during bathing presents a challenge. Devices that can be worn during bathing, such as waterproof ECG patches, have been developed, but like smartwatches, their usage depends on the wearer’s risk awareness and compliance.

Complementing Wearable Devices with Unconsciously Measurable Life Built-in Sensors

The ideal solution would seamlessly integrate health monitoring into everyday activities without requiring conscious effort from the individual. For situations prone to sudden death, integrating sensors into household items such as bathtubs, beds, toilets, and furniture could passively collect cardiac signals. There has been research into bathtubs capable of measuring heart and respiration rates, and even capturing ECG signals. Beds and toilet bowls capable of measuring ECGs have also been developed. Embedding sensors into everyday objects allows for the continuous, unconscious collection of heart data.

Integrating Data from Various Specifications of Wearable Devices and Multiple Life Built-in Sensors: The Crucial Role of Mother AI

The combination of wearable devices and sensor-equipped home monitoring demonstrates the feasibility of continuously gathering vital health information throughout daily life. However, the challenge lies in the varied nature of the sensors and the lack of uniformity in the data they collect. This is where the integration capability of AI becomes crucial. A comprehensive monitoring AI, which I have previously referred to abstractly as “Mother AI,” would play a key role in synthesizing this disparate data, ensuring effective health monitoring and intervention when necessary.

For more details, visit PURSUING TECHNOLOGY TO CREATE A WORLD WHERE EVERYONE’S MENTAL AND PHYSICAL HEALTH IS MONITORED: THE WORLD WATCHED OVER BY MOTHER AI

The Second-Best Solution for Preventing Sudden Death at Home: Life-Saving Home Monitoring Based on the Indicator of Falling and Mutual Aid

Developing Sensors to Detect Falls with Privacy Consideration

While ventricular fibrillation prediction is believed to be achievable, it might take time. A second-best approach, however, is available beforehand. When ventricular fibrillation occurs, an individual loses consciousness and collapses within six seconds, leaving no time to call for emergency services themselves. Nonetheless, if this collapse could be detected and alerted, it would enable others to take action. Surveillance cameras installed throughout the home, including in the living room, bathroom, bedroom, and toilet—areas where episodes are likely to occur—could serve this detection purpose. However, privacy concerns pose a significant barrier. No one wants their bathing or toileting moments to be observed. A solution exists in lowering the resolution of cameras so they can’t discern individuals’ faces or what they are doing, possibly using infrared cameras to differentiate between people and objects. While privacy is preserved, technology capable of accurately recognizing a person’s collapse should be developed.

The Current Potential of Japan’s Home Security Services

In Japan, security companies like SECOM and ALSOK offer surveillance services for the elderly. They provide exceptional services by installing sensors along frequently used pathways (like toilets) to send automatic alerts to the security company if no movement is detected over a certain period. Additionally, they offer pendants that, when squeezed, immediately send an emergency call to the security company. Though squeezing a pendant might be feasible within six seconds of ventricular fibrillation onset, home security services, as helpful as they are for many domestic issues, are insufficient for saving lives from sudden cardiac arrest. This insufficiency stems from the time it takes for response staff to arrive—between five to fifteen minutes—after an emergency signal is sent to the security company, making it challenging to use an AED within the crucial five minutes for saving a life from ventricular fibrillation. Furthermore, the time lost confirming the absence of movement adds another painful dimension to the challenge of saving lives from ventricular fibrillation. Improvements in these two areas could potentially increase the probability of successful resuscitation significantly.

Mutual Aid Is the Only Option After Collapse

After a collapse, even if emergency services or security companies are contacted, it is challenging to ensure their arrival within five minutes. Therefore, the initial life-saving actions must be taken by those present on the scene. For homes, this means neighbors and nearby residents play a pivotal role in emergency response. While a future where isolation robots perform AED application and CPR might exist, it seems far off. If a cohabitant notices a sudden cardiac arrest at home, they become the person most capable of providing immediate CPR. For individuals living alone or when cohabitants are absent, notifying emergency services or security companies upon experiencing a cardiac arrest means that, apart from professionals, people nearby who can arrive within a minute must be informed to undertake life-saving actions. Thus, merely developing technologies to detect collapses is insufficient without a mutual aid network system for emergencies among neighbors. Emergency and security companies should work in collaboration with these mutual aid systems, acting as a command center.

Constructing a “Home Monitoring × Mutual Aid System” in Japan Amid Rising Solo Living and Lonely Deaths

The Reality of Lonely Deaths in Japan

Exploring the concept of lonely deaths, it’s estimated that 30,000 people die alone in Japan each year. The causes of these lonely deaths are primarily diseases (66.8%) and suicide (9.8%). With an increasing number of elderly living isolated lives, they pass away without being noticed, sometimes only discovered post-mortem. The average time taken to discover these lonely deaths, according to the Japan Small Amount and Short Term Insurance Association, is 17 days for both men and women. However, women tend to be discovered more quickly than men, with 38.4% of men found within three days compared to 50.1% of women. This sad reality underscores a deep societal issue beyond the scope of mere living arrangements but poses a significant barrier to preventing sudden deaths at home from the perspective of lonely deaths increasing in Japanese society.

The Current State of Monitoring Elderly as an Alternative to Family in Japan

Traditionally, multi-generational living was common in Japan, ensuring that lonely deaths were rare as family members would quickly notice any issues. Today, however, with more elderly people living isolated from society, there’s a pressing need for alternative monitoring systems. One such previously mentioned answer is the home security services provided by companies like SECOM and ALSOK , which offer monitoring for elderly parents, alerting contracted children in emergencies. Yet, only a small fraction of people, approximately 4% of households with elderly members living separately, use this service. Another option is nursing homes, where elderly residents live in a communal setting under professional supervision. Despite this, many seniors either cannot afford or choose not to live in such facilities. The Cabinet Office’s Special Team on Loneliness and Isolation reports that the solitary living rate among the elderly was 31.5% in 2015, projected to reach 40% by 2040. This indicates a significant portion of the elderly population remaining unmonitored.

Diverse Societal Cultures in Preventing Lonely Deaths: The Example of China’s Mutual Aid Network

China, having undergone rapid economic development and large-scale urbanization, faces a dilution of traditional community bonds similar to urban Japan. However, lonely deaths are reportedly less common in China, attributed to the government’s swift efforts in building and maintaining communities. Particularly, the “Resident Committee,” a government entity close to the citizens’ daily lives, actively monitors the elderly living alone. Moreover, an “Mutual Aid Network System” exists, formulated by the Shanghai government in 2018 as part of the “Support for Informal Caregiver System.” This initiative encourages community residents to support the elderly through phone check-ins and home visits, with the government providing regular training and education to those offering services. This Chinese model is considered to work advantageously as a foundation for the mutual aid system necessary to prevent sudden death at home.

Japan’s Historical Mutual Aid System

During the Edo period, dense wooden housing in Edo (Tokyo) made fire a constant threat, leading to community-based fire prevention efforts, including “night rounds” where residents would patrol their neighborhoods to warn against fire hazards. This historical practice of mutual aid could serve as a foundation for a modern system to prevent sudden deaths, highlighting the potential of reviving and adapting traditional mutual aid practices to contemporary societal needs.

The Future of People and Technology Watching Over in Place of Family

In contemplating ways to save lives from sudden death at home, it has become evident that overcoming extremely high hurdles is necessary to solve this problem. The first solution that comes to mind is the development and enhancement of built-in sensors that measure the body’s condition unconsciously during daily life, essentially a health version of the smart home concept. It was thought that developing a monitoring system with Mother AI, which collects and integrates health information from various sensors in real-time, watches over health, and prompts individuals to take action to maintain their health when necessary, would be essential. This development becomes crucial, especially as the number of single-person households, particularly among the elderly, is predicted to continue increasing. It’s emphasized that the creation of a health-oriented smart home to prevent sudden death should not be the endeavor of a single company but requires the collaboration of many companies involved in daily life activities.

However, it has become clear that saving lives from cardiac arrest cannot be achieved through technology alone, but requires a mutual aid system where neighbors help each other. The more technology progresses, the more it brings into question the most human aspect: the way of communal living, presenting a paradox and an intriguing situation. In the end, it’s all about human interaction. Only by revitalizing the spirit of mutual assistance, which fades with urbanization and the modern world, can we achieve an improvement in the survival rates from sudden death.